by Hans DePold, town historian

(Written in May 2014, for the 100th Anniversary of Bolton Town Hall, formerly Bolton Grange Hall)

For many years, Bolton Town Hall was also used as the Bolton Grange Hall. The ultimate objective of the Bolton Grange was the mutual instruction and development of both its members and the agrarian rural community. It strove to lighten the load of farmers and rural folk by introducing and discussing the latest farm technology and by sharing knowledge of agriculture, animal husbandry, and farm machinery. In addition, the national charter's purpose stated it was to expand the minds of its members while tracing the beautiful laws that the Great Creator had established in the universe, and to enlarge their views of creative wisdom and power.

The Bolton Grange was formed on May 21, 1886, and according to its account book's first entry, it began with 14 charter members: William C. White, Horace Wetherell, Julia S. Loomis, Charles E. Carpenter, Fanny J. Sperry, William E. Alvord, George Curtis, Charles E. Sperry, William W. Loomis, Eliza L. Sperry, Charles N. Loomis, Lizzie C. Loomis, William H. Loomis, and Mrs. William Loomis.

The Grange was considered an agricultural family or fraternity. Historically, it promoted building rural America through grassroots activities. It had several varied agendas because the Grange was a conglomeration of interests. It was a shared vision to empower and improve the opportunities of agricultural people by offering a formal support group to address agricultural concerns and to reinforce family values in the context of religious heritage. The organization and ritualism of the Grange was rooted in the structure of old English estates, which produced most of England's food until the 1900s.

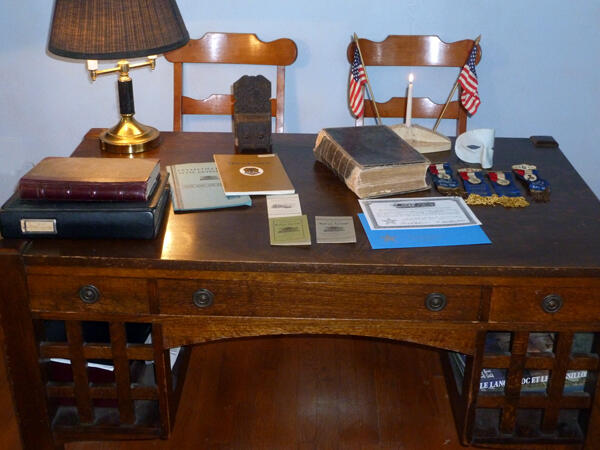

The TV series "Downton Abbey" shows the English estates at the time of their decline, when the English government was breaking up the estates because they no longer produced enough food. The estates were complete unto themselves and represented a type of individualism quite distinct from the American farm estate. The Grange Master's desk was symbolic of the baronial castle that was reached through a broad expanse of trees. The estate's fields that composed the farm were called granges. American Grange officers were representative of the officers of the English estates and included the Gate Keeper, the Overseer, the Lecturer, the Steward, and the Chaplain. The organization of the estate was evident in the physical designations of each of the officers' seats within the Grange Hall. This traditional organization acted to buttress the internal structure and authority of the American Grange. So in a very real sense the Grange filled an ancient educational and hierarchical role, when ancient landowner estates were as big as or bigger than the town of Bolton.

While emphasizing the relationship between agricultural life and moral development, the Grange employed fraternal rituals based upon symbols relevant to the art of farming. The booklet, "Field Assistant to the National Master," says that the "...teachings of the ritual enable our Order to be political without being partisan, religious without being denominational, and though it binds its members with a strong fraternal tie, it assures the member's complete individuality."

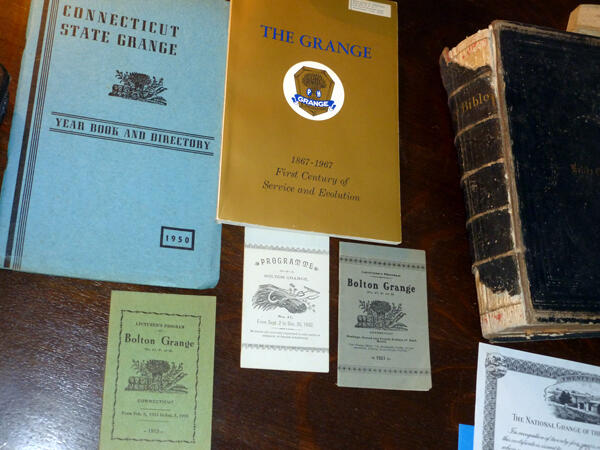

Grange ritualism began at the local level, and at its most basic was organized into seven degrees, the first four of which were the seasons of the year: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The county Grange offered the Fifth Degree, the State Grange the Sixth Degree, and the National Grange, the Seventh. These latter three degrees were those of Pomona, Flora, and Ceres or Demeter. W.L. Robinson, author of "First Century of Service and Evolution: The Grange, 1867–1967," relates that "[t]hese degrees are available to all those who fully subscribe to the long-established custom of teaching by symbols and emblems, to the principle of using the power of ritualism to bring out the finer characteristics of the members and the beauty of rural life."

The Bible was put on the symbolic Grange Master's desk in the middle of the Grange Hall during meetings and was opened at the start and closed at the end of the gatherings. A prayer was usually said at these times as well. While the Grange was not a religious organization per se, at the Grange the Bible and God were considered present at all meetings. A lit candle was often placed between two small American flags on the desk. Each January a small booklet was written and distributed with the meeting schedules and agendas for all the planned meetings of the year. Honors for Grange achievements were given both with medals and citations.

National Grange rules suggested meeting at least once a month for both local and county Granges. Both met independently of each other and were forums for public discussion. Grange policy decisions, also referred to as resolutions, began at the local level because it was recognized that what worked in Tolland County did not always work in Hartford County. The resolutions reflected community interests and concerns about conservation, safety issues, development, farm policy, rural businesses, health inspections, commodities, farm credit, pesticide and chemical uses, and disease control and animal care, to name only a few. Resolutions were revised and refined by state Grange annual sessions and were reviewed and voted on by delegates at the annual national Grange meeting.

The Grange effectively sought improvement in federal crop insurance programs and assistance in the reorganization of the government's trade functions. The Grange was active in opposition to the selling of insurance by financial institutions, won change on on-farm storage loan programs, and gained legislation to assist the small family farm operator. Moreover, the Grange participated in the activities of the Trade Policy Advisory Committees, the USDA Ag-Land Study Groups, the Pesticide Users Conferences, the Policy Advisory Committees for Highway Users, the President's Committee for the Employment of the Handicapped, and the National Safety Council. Grange members involved themselves in alleviating the needs of their respective communities by engaging in service work.

The beauty and effectiveness of the Grange was a product of its origins. As an ideologically oriented organization, the Grange actively reinforced the values prevalent within a rural environment. Most states had active Granges. The changing character of the Grange reflected the fact that it was no longer exclusively dependent on farmers for its membership. The Bolton Grange sought to examine and satisfy the interests of its community, a rural community where farm values were a part of everyday family life, but the Bolton Grange also sought to involve people of all ages and walks of life in its activities. Junior Grange membership began at age 5 and continued until the age of 14, when a young member could be inducted into the Bolton Grange.

And while the Grange originally began with farm families concerned about the effects of the aftermath of the Civil War and Reconstruction on their daily lives, war times and economic depressions came and went. It was the Grange that fought the monopolies of railroads and their high user rates for transporting food to the cities. The Grange led the effort to stop all monopolies and the robber-baron financial tycoons from exploiting and destabilizing the economy. Ironically, the success and greater efficiency of farming as the 20th century progressed was the undoing of the Grange; the American population went from being comprised of 90 percent employed in farming occupations to less than 10 percent, and thus the Grange eventually lost its voting influence in Congress.

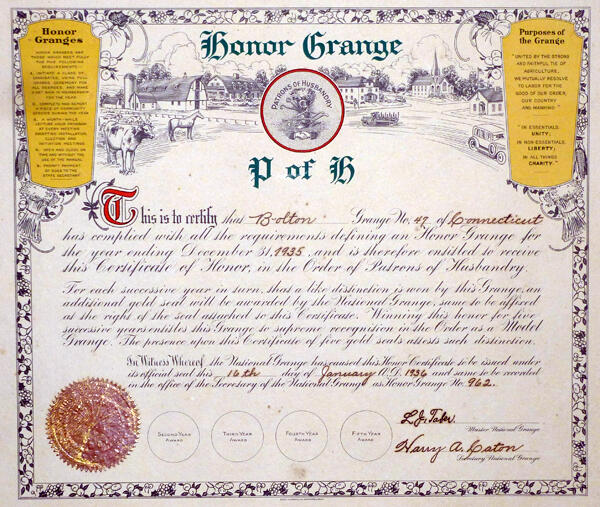

In 1936 the Bolton Grange received a Certificate of Honor from the National Grange and became an Honor Grange and was recognized as a model Grange in America.

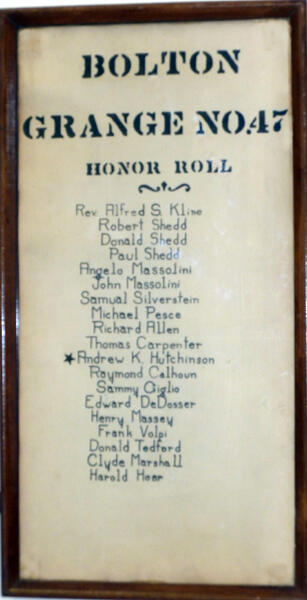

During WWII, penicillin began being administered to patients, but not in time for all who could have used it. Eighteen Bolton Grange members enlisted to fight in WWII and one Bolton Grange warrior died during training. The plaque in Town Hall and the banner were made by Bolton Grange members. There is a star for each Grange member who served. The special star signifies the warrior who did not return, Andrew Keeney Hutchinson, a Navy cadet pilot in training.

The Bolton Grange remained active until June 1978 because of its deep concern for protecting a most valuable way of life. Membership dues in 1886 were $1 per year, and by the time an official dues book was used in 1949 the dues had risen to $2 per year. The dues were $3 per year from 1955 until the Bolton books were closed. At times there were also members from Andover, Manchester, Coventry, East Hartford, and Glastonbury. The last two regular dues entries were for the third quarter of 1977.

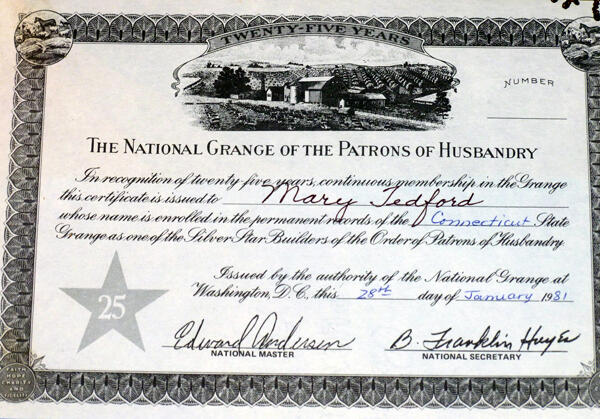

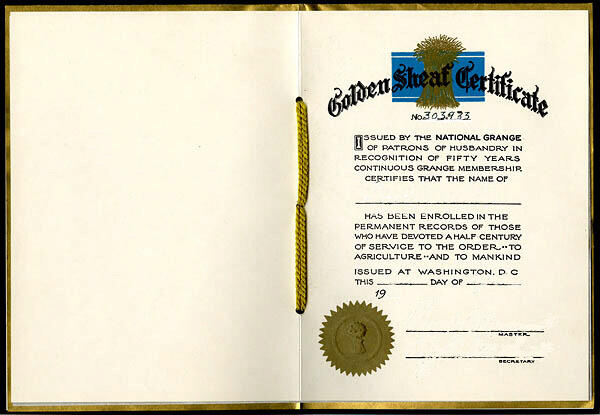

The Silver Sheaf Certificate was earned after 25 years, and the Golden Sheaf Certificate was earned with 50 years of Grange service. Several of both certificates were earned by Bolton members but only one is currently in Bolton's possession. Jane Maneggia kept the final records of the Bolton Grange for many years. Her sister Mary Tedford continued serving in the Manchester Grange after the Bolton Grange was no longer active, and she received a Silver Certificate in 1981. She also preserved the Bolton Grange artifacts and books for the town of Bolton and then gave them to the town historian.