by Hans DePold, Bolton Town Historian

(Published in the Bolton Community News, February 2007)

Their whips were impressive instruments of encouragement, guidance, and motivation. Bullpunchers, with little more than sheer muscle and sinew, were the tough, rock-hard men who helped wrestle logs out of the Bolton woods and stones from the Bolton Quarry and then hauled them to build and heat the city of Hartford.

The French Army brought approximately 1,600 oxen pulling 400 wagons through Bolton in 1781 and on their return in 1782. They also had several hundred horses primarily for riding and pulling carriages. The animals were put to maximum use. When an ox or horse died it usually was from old age and exhaustion, so they naturally had rather tough meat. The day they died, the army and families on the trail had beefsteak served after the dead ox or horse was tenderized. That is where the expression, "to beat a dead horse" comes from. They beat the dead horses and dead oxen to tenderize them before preparing them.

By 1850 New England was in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. The highlands of Bolton were the watersheds that supplied power to run mills in Tolland and Windham. But Bolton was without the waterpower to do much more than run a few sawmills. Shoddy Mill and Stony Road were sawmill sites, along with Camp Johnson. The primary power and moving force in Bolton in those days was the ox. Oxen were gelded bulls, not known for their speed because the most dangerous bulls were usually slaughtered very young for veal. It was the bullpuncher who persuaded the oxen to move, and he was not delicate about it. The loudest sound in Bolton, in those days, was the bellowing of the bullpuncher as he goaded and prodded the phlegmatic former bulls. The bullpuncher had his plugs of chewing tobacco, his whiskey, and his own type of profanity. They were colorful, roaring, and could spit brown sticky tobacco juice with what the children spectators considered enviable accuracy. And so curious children usually kept their distance and learned not to taunt the bullpunchers.

A road grader in those days consisted of at least four oxen pulling a large quarry stone that leveled the road. The grader gradually lowered the road level, so that over time dirt roads would move up to 400 feet sideways as the bullpuncher sought better road drainage.

The bullpuncher often was tempestuous and impatient, and if the load was great he might run up and down the long line of oxen, jabbing them with his goad stick while furiously roaring insults at them. He always kept an eye on the eyes of the restless brutes because with a swing of the ox's head or the lashing out with its hind leg, a man could be crippled or killed. The bullpuncher knew that when ox's eyes rolled back, he had to jump back since the beast would then kick out. The oxen had to be tough to survive but the men were even tougher.

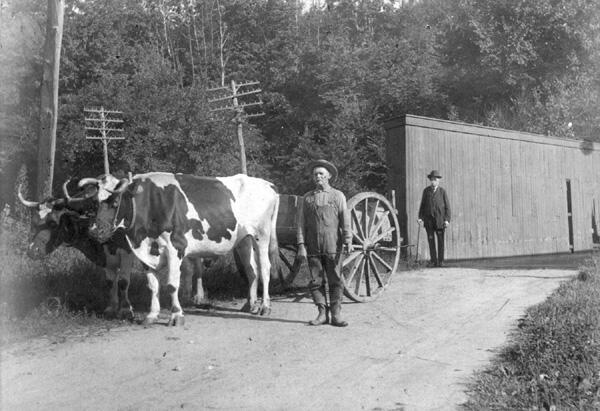

George Stanley is shown here in the first photo with his oxen on Hop River Road in Bolton in the early 1900s. He would haul lumber and logs through Bolton to Hartford. Children stayed out of his spitting range, which for him was said to be about ten yards. In the second photo, Bolton farmer Marvin Howard and his team of oxen are shown in a 1920 photo at Notch Road at the bridge over the railroad tracks. Oxen more than horses were used to pull plows and wagons because they were steady and the right speed for our rough roads and fields. Horses were primarily for riding on wider smoother roads where speed was an option. But with the invention of the internal combustion engine the days of oxen were numbered.

Richard Rose likes to tell a story about farmer Kneeland Jones, the last ox-pull county fair champion from Bolton to enter his oxen in the sled pulling contests. It is the story about when Richard learned to keep his distance. Richard had a small bicycle as a young teenager and one day he saw Kneeland driving his team down Bolton Center Road. Pedaling feverishly he almost made one pass around Kneeland and his team when Kneeland began bellowing at him. That only tempted him to attempt a second pass. As soon as he started the second pass Richard Rose felt the whip snap much, much too close for comfort, and was off like a bolt. The whip was an impressive instrument of guidance and motivation.