by Hans DePold, town historian

(Published in the Bolton Community News, February 2008)

Charley's story began with some original research that Bolton resident John Maston did at Bentley Library about Charley's good luck. I then had the good fortune to locate a New York Times article from May 13, 1883, the papers of Booker T. Washington, a book on Teddy Roosevelt, and finally a 1906 book titled "Men of Mark in America." All fill in the incredible life of this once nationally known Bolton Civil War hero.

Born April 10, 1843, to Jacob and Dorcas Lyman of Bolton, Charles Lyman attended a one-room schoolhouse in Bolton during the winter and worked as a farmhand during the summer. By age 16 he was a teacher at the Bolton Birch Mountain Schoolhouse. At age 19 he finished his formal education, taking one term at Rockville High School and then volunteering to fight in President Lincoln's army July 21, 1862.

Born April 10, 1843, to Jacob and Dorcas Lyman of Bolton, Charles Lyman attended a one-room schoolhouse in Bolton during the winter and worked as a farmhand during the summer. By age 16 he was a teacher at the Bolton Birch Mountain Schoolhouse. At age 19 he finished his formal education, taking one term at Rockville High School and then volunteering to fight in President Lincoln's army July 21, 1862.

Forty-eight Bolton young men, roughly 7 percent of Bolton's population, marched off as parts of four regiments. The 16th was the Hard Luck Regiment; the others were just luckless. There were no lucky divisions, just survivors. Charles was in the 14th and they were called to duty on August 20, 1861, just four days before the Hard Luck Regiment. They had almost no training when they arrived for the battle of Antietam (Sharpsburg), Maryland, the bloodiest single-day battle in American history. Fortunately the Bolton soldiers, with their education, hard farm work, self-reliance, survival skills, and hunting skills, were somewhat prepared to survive the war.

Charley, a corporal, was almost killed on his first day of battle on September 17, 1862.The 14th Regiment was advancing in a suicide charge when a Confederate shell burst less than 3 feet from Charley, killing four and wounding five others and stunning, but only scratching, Charley. The lucky dust of Bolton was still on him. After picking up body parts and burying the dead, Charley was shipped off to fight at Fredericksburg, Virginia. But the commanders had noticed how skilled and calm Charley was, and unbeknownst to him they already were starting paperwork to make him a 2nd Lieutenant.

On December 13, 1862, the 14th Regiment was at Fredericksburg in another suicide charge on a Rebel position at Marye's Heights. Charley was so focused that he did not notice his regiment was already retreating under the withering fire. The four in this unit closest to him had fallen further back and he was within about 200 yards of the Rebel camp command post, not knowing he was alone. Then he saw a Confederate officer come out of his command post, which was in the Stevens house. Charley fired twice and missed the officer but attracted attention as if he had thrown a hornet's nest into the Rebel camp.

Bullets were buzzing around him as he finally stopped advancing and stood behind a 4-inch wide fence post just in time for the post to stop a bullet from hitting him in the stomach. Charley was too focused on shooting that Rebel officer to notice that he was now the only Union soldier fighting the entire Rebel army. He rested his rifle on the post to steady his aim, but before he could squeeze the trigger a bullet struck the stock of his rifle and flew over his right shoulder. Again he took aim and fired a third round and hit the officer. Now the Rebels were really angry because the officer was General Cobb, who rapidly bled to death. Charley at last looked around and saw he was the only one the Rebels were shooting at because the others were almost back to safety. He wrote, "Bullets were flying very thick about me and I had no expectation of getting off the field alive, as it was fully 300 yards to the nearest cover."

Charley ran toward a canal where there was a foundation that had been dug for an icehouse. A bullet went through his haversack and the skirt of his overcoat, and a shell burst right over his head. Just before he reached cover, he felt as though a horse had kicked him in the back. Charley dropped into the hole. He had been shot in the back.

Fortunately, Charley had been carrying all his heavy equipment on his back all day and the musket shot spent its energy tearing through 14 layers of his wool blanket and did not touch him. But Jerry Gready from Vernon was in that hole, too, and as he fled the field a bullet entered his heel and came out between his toes. Charley attended to him and about 100 wounded men for the rest of the day, and when darkness fell he carried Jerry on his back to the Union field hospital.

By February of 1863, Charles Lyman was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant and, unbeknownst to him, his papers for his promotion to 1st Lieutenant were already in the works. But more remarkably, 20-year old 2nd Lt. Charles Lyman was immediately put in command of a different company, passing over 1st Lieutenants and experienced soldiers, some of whom were jealous, had high connections, and began plotting against him. This was the worst thing and the best thing that happened to him at that time.

When in the next battle a young man named Starkey died, his father, who had fought side by side with his son, asked Lt. Charles Lyman for a leave of absence to bury his son and asked him to write a short obituary. Charley showed the other officers what he had written and they all agreed that it was a common practice and that it did not violate any new orders. But when he gave it to Starkey's father, Charley found himself court-martialed. One of the jealous officers took the letter from Starkey's father and sent it to the War Department, claiming Charles Lyman had violated the most recent secrecy orders.

The War Department acted without a hearing or telling Charley the specific charge. It was a time when the War Department was rounding up Union deserters and putting them in front of firing squads, and the first draft of soldiers was being considered. Charley didn't think it was wise to make trouble by asking what the charge was, so he ended up with a dishonorable discharge on May 12, 1863 after only nine months of active duty. At the age of 20, he was back teaching young ladies. Truly, Charley's bad luck was what half the young soldiers were longing for at that moment in history.

Charley married Amelia Campbell of Hartford in 1865 and they had two children. He attended a business college and landed a Washington, D.C., job in the Treasury Department. Once in Washington he resolved to clear his name with the help of officers who knew of his heroism and who had promoted him. He wrote directly to President Grant and within a few days his dismissal was revoked and he received his honorable discharge. In 1872 President Grant appointed him to the job of civil service examiner for the Treasury. In 1875 he graduated as class valedictorian of National University Law School. President Arthur promoted him to chief examiner. President Cleveland promoted him to the Civil Service Commission.

President Harrison reappointed him to the Civil Service Commission along with young Theodore Roosevelt. Together with Teddy Roosevelt he cleaned out government of corruption and cronyism. When corrupt politicians tried to smear his name by saying he had been dishonorably discharged, the New York Times came to his defense on May 13, 1883. He was the commission chairman from 1886 to 1893. This commission established the first merit system for federal workers whose jobs previously had gone to political hacks appointed for their support in political campaigns. Later, he served as the Chief of Appointments for the Secretary of the Treasury.

Charles Lyman became a friend of Teddy Roosevelt, belonged to the Sons of the American Revolution, the Evangelical Alliance, and the Washington City Bible Society, and was an active member of the Republican Party. Booker T. Washington's papers show that after the Civil War Charles Lyman helped him find jobs for educated former slaves. He is a son of Bolton of whom we can all be proud.

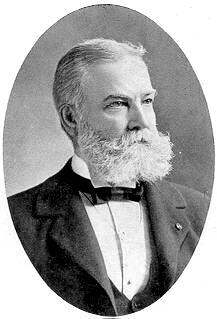

His biography was published in 1906 in a two-volume book titled, "Men of Mark in America." He said his first decisive impulse to strive for excellence came in Bolton from a "good woman, his school teacher in early childhood." He said, "The best part of my education has come from private study, and doing important tasks thrust upon me without special preparation; and from contact with men and affairs."

To young Americans he says: "A man should love his God, his country and his fellows; love and practice truth, honesty and virtue."

Read More: